Nature: A God by Another Name

“Worship” by Charles Sprague Pearce. A symbolic depiction of early reverence, often interpreted as humankind’s spiritual reverence for nature—an idea explored and critiqued in this article.

There’s a curious trend in modern discussions about nature and origins: many of the same people who reject the idea of a Creator can’t seem to stop speaking as if one exists. They disavow religion, mock belief in a divine Designer, and insist the universe is the product of blind, material processes. But then they describe nature with words that reveal something entirely different.

Nature, we’re told, “selects,” “optimizes,” “invents,” “engineers,” and even “teaches.” It is praised for its problem-solving ability, for creating the most elegant and efficient designs. For decades, however, nature was dismissed as chaotic, imperfect, and full of errors. This view was essential to the Darwinian argument. Critics of intelligent design insisted that no designer would have made something so “flawed.”

Yet in a remarkable narrative reversal, the same nature once mocked as clumsy is now admired for its engineering excellence. Entire industries are being shaped by biomimicry: the study and imitation of biological systems for human innovation. From self-cleaning surfaces modeled on lotus leaves to ultra-strong materials inspired by spider silk, engineers and scientists are openly imitating what nature “figured out.”

What was once evidence against design is now treated as evidence of genius. But if nature is so full of intelligence and solutions, the question must be asked: Where did that intelligence come from?

This shift has created a strange irony. Nature has become a kind of secular deity, one that demands no obedience, offers no moral law, and but is praised for its infinite creativity and wisdom.

This tendency reveals something deep in the human mind: we instinctively attribute agency to order. We don’t really believe that complex, functional systems arise by accident. So even those who reject God often end up personifying the natural world, giving it intention, intelligence, and power.

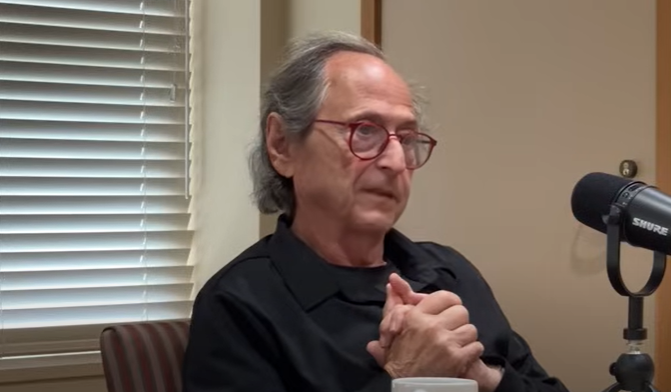

Even prominent scientists have begun to echo this thinking. In a YouTube interview, Nobel laureate Michael Levitt, an expert in structural biology, described what he calls “biological intelligence.” He didn’t use the term metaphorically. He credited biology itself with invention and ingenuity:

“Biological intelligence is the big one. It invented the molecules that made life possible. It invented the schemes of evolution. It invented all sorts of amazing things…

The machine assembles itself. And all of biology... it’s all done by itself.

We did not create biology. And therefore it’s an alien form of intelligence from which we can learn a great deal.”

Levitt’s language points to a layered, almost trinitarian nature: one part that exists, one part that creates, and one part that instructs. It’s something within nature that predates it, devises its molecules, and instills its intelligence.

In elevating nature to this role, the line between science and metaphysics no longer exists. Nature becomes an intelligence that resides outside of biology—an unseen force that designs biological systems without being one.

Levitt’s words make one thing clear: nature is being described in terms that imply design, intelligence, and intentionality—while the scientific community still officially denies all three.

I explore this paradox in depth in Chapter 25, “ID by Another Name,” of my book, Natural Technology, where I unpack how the language of modern science has become increasingly theological in everything but name.

The idea that nature could possess superior engineering is no longer controversial—it’s celebrated. Engineers praise it. Designers study it. Scientists try to decode its secrets. What they once dismissed as accidental, they now imitate.

Many speak of Nature with a level of reverence and attribution that borders on worship. They insist they are non-theists, yet the way they describe nature—its creativity, its wisdom, its power to design and teach—suggests otherwise. This becomes especially clear in modern fields like biomimicry, where scientists openly marvel at nature’s "ingenuity" and "solutions." Figures like Janine Benyus speak of nature as a teacher, even a guide— assigning to the natural world the traits they claim are foreign to their worldview.

Still, they stop just short of admitting the obvious: what they call ‘nature’ bears all the marks one would expect from intelligent design—not as a designer itself, but as the product of one. Strangely, this deaf, blind, and mute creator is still regarded as the most intelligent of all.

They will not say “design,” so they say “emergence.” They will not say “Creator,” so they say “nature.”

When you strip away the posturing, the academic language, and the philosophical evasion, you’re left with this: modern science is full of people who cannot stop describing design—even when they deny a Designer. They are confessing without meaning to.

We’re told that consciousness is a recent arrival on the evolutionary timeline. A fluke. Yet somehow, this unconscious, pre-conscious nature produced systems so advanced they leave our brightest minds scrambling to reverse-engineer them.

Think about that.

The very same nature that supposedly emerged from a mindless explosion is now being studied for its architectural brilliance, chemical precision, and problem-solving sophistication. How does an unintelligent process outperform intelligent ones? If a Boeing 747 implies an engineer, what does a hummingbird imply?

The answer, according to many, is still “nothing.”

But that’s not honest. If any human had produced what nature has (cellular replication, self-healing tissues, error-checking enzymes, photosynthetic conversion) he’d be called a genius. Nature does it, and she’s called a lucky Engineer.

For questions for S. A. Cooper, or if there’s a topic you’d like him to cover, you can send a message here.

Follow me on Facebook for updates and new articles.